Summary: High risk, low reward: A challenge to the astronomical value of existential risk mitigation

This is a summary of the GPI Working Paper “High risk, low reward: A challenge to the astronomical value of existential risk mitigation” by David Thorstad. The paper is now forthcoming in the journal Philosophy and Public Affairs. The summary was written by Riley Harris.

The value of the future may be vast. Human extinction, which would destroy that potential, would be extremely bad. Some argue that making such a catastrophe just a little less likely would be by far the best use of our limited resources--much more important than, for example, tackling poverty, inequality, global health or racial injustice.1 In “High risk, low reward: A challenge to the astronomical value of existential risk mitigation”, David Thorstad argues against this conclusion. Suppose the risks really are severe: existential risk reduction is important, but not overwhelmingly important. In fact, Thorstad finds that the case for reducing existential risk is stronger when the risk is lower.

The simple model

The paper begins by describing a model of the expected value of existential risk reduction, originally developed by Ord (2020;ms) and Adamczewski (ms). This model discounts the value of each century by the chance that an extinction event would have already occurred, and gives a value to actions that can reduce the risk of extinction in that century. According to this model, reducing the risk of extinction this century is not overwhelmingly important––in fact, completely eliminating the risk we face this century could at most be as valuable as we expect this century to be.

This result––that reducing existential risk is not overwhelmingly valuable––can be explained in an intuitive way. If the risk is high, the future of humanity is likely to be short, so the increases in overall value from halving the risk this century are not enormous. If the risk is low, halving the risk would result in a relatively small absolute reduction of risk, which is also not overwhelmingly valuable. Either way, saving the world will not be our only priority.

Modifying the simple model

This model is overly simplified. Thorstad modifies the simple model in three different ways to see how robust this result is: by assuming we have enduring effects on the risk, by assuming the risk of extinction is high, and by assuming that each century is more valuable than the previous. None of these modifications are strong enough to uphold the idea that existential risk reduction is by far the best use of our resources. A much more powerful assumption is needed (one that combines all of these weaker assumptions). Thorstad argues that there is limited evidence for this stronger assumption.

Enduring effects

If we could permanently eliminate all threats to humanity, the model says this would be more valuable than anything else we could do––no matter how small the risk or how dismal each century is (as long as each is still of positive value). However, it seems very unlikely that any action we could take today could reduce the risk to an extremely low level for millions of years––let alone permanently eliminate all risk.

Higher risk

On the simple model, halving the risk from 20% to 10% is exactly as valuable as halving it from 2% to 1%. Existential risk mitigation is no more valuable when the risks are higher.

Indeed, the fact that higher existential risk implies a higher discounting of the future indicates a surprising result: the case for existential risk mitigation is strongest when the risk is low. Suppose that each century is more valuable than the last and therefore that most of the value of the world is in the future. Then high existential risk makes mitigation less promising, because future value is discounted more aggressively. On the other hand, if we can permanently reduce existential risk, then reducing risk to some particular level is approximately as valuable regardless of how high the risk was to begin with. This implies that if risks are currently high then much larger reduction efforts would be required to achieve the same value.

Value increases

If all goes well, there might be more of everything we find valuable in the future, making each century more valuable than the previous and increasing the value of reducing existential risk. On the other hand, however, high existential risk discounts the value of future centuries more aggressively. This leads to a race between the mounting accumulated risk and the growing improvements. The final expected value calculation depends on how quickly the world improves relative to the rate of extinction risk. Given current estimates of existential risk, the value of preventing existential risk receives only a modest increase.2 However, if value grows quickly and we can eliminate most risks, then reducing existential risk would be overwhelmingly valuable––we will explore this in the next section.

The time of perils

So far none of the extensions to the simple model imply reducing existential risk is overwhelmingly valuable. Instead, a stronger assumption is required. Combining elements of all of the extensions to the simple model so far, we could suppose that we are in a short period––less than 50 centuries––of elevated risk followed by extremely low ongoing risk––less than 1% per century, and that each century is more valuable than the previous. This is known as the time of perils hypothesis. Thorstad explores three arguments for this hypothesis but ultimately finds them unconvincing.

Argument 1: humanity’s growing wisdom

One argument is that humanity's power is growing faster than its wisdom, and when wisdom catches up, existential risk will be extremely low. Though this argument is suggested by Bostrom (2014, p. 248), Ord (2020, p. 45) and Sagan (1997, p. 185), it has never been made in a precise way. Thorstad considers two ways of making this argument precise, but doesn’t find that they provide a compelling case for the time of perils.3

Argument 2: existential risk is a Kuznets curve

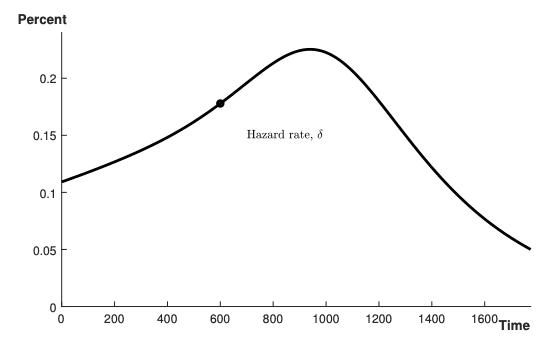

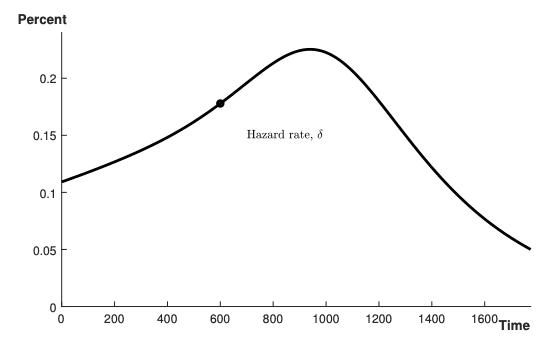

Figure 1: the existential risk Kuznets curve, reprinted from Aschenbrenner (2020).

Aschenbrenner (2020) presents a model in which societies initially accept an increased risk of extinction in order to grow the economy more rapidly. However, when societies become richer, they are willing to spend more on reducing these risks. If so, existential risk would behave like a Kuznets curve––first increasing and then decreasing (see Figure 1).

Thorstad thinks this is the best argument for the time of perils hypothesis. However, the model assumes that consumption drives existential risk, while in practice technology growth plausibly drives the most concerning risks.4 Without this link to consumption, the model gives no strong reason to think that these risks will be reduced in the future. The model also assumes that increasing the amount of labour spent on reducing existential risks will be enough to curtail these risks––which is at best unclear.5 Finally, perhaps even if the model is correct about optimal behaviour, real world behaviour may fail to be optimal.

Argument 3: planetary diversification

Perhaps this period of increased risk holds only while we live on a single planet, but later, we might settle the stars and humanity will be at much lower risk. While planetary diversification reduces some risks, it is unlikely to help us against the most concerning risks, such as bioterrorism and misaligned artificial intelligence.6 Ultimately, planetary diversification does not present a strong case for the time of perils.

Conclusion

Thorstad concludes that it seems unlikely that we live in the time of perils. This implies that reducing existential risk is probably not overwhelmingly valuable and that the case for reducing existential risk is strongest when the risk is low. He acknowledges that existential risk may be valuable to work on, but only as one of several competing global priorities.7

Footnotes

1 See Bostrom (2013), for instance.

2 Participants of the Oxford Global Catastrophic Risk Conference estimated the chance of human extinction was about 19% (Sandberg and Bostrom 2008), and Thorstad is talking about risks of approximately this magnitude. At this level of risk, value growth could make a 10% reduction in total risk 0.5 to 4.5 times as important as the current century.

3 The two arguments are: (1) humanity will become coordinated, acting in the interests of everyone; or (2), humanity could become patient, fairly representing the interests of future generations. Neither seems strong enough to reduce the risk to below 1% per century. The first argument can be criticised because some countries already contain 15% of the world's population, so coordination is unlikely to push the risks low enough. The second can also be questioned, because it is unlikely that any government will be much more patient than the average voter.

4 For example, the risks from bioterrorism grow with our ability to synthesise and distribute biological materials.

5 For example, asteroid risks can be reduced a little with current technology, but to reduce this risk further we would need to develop deflection technology––technology which would likely be used in mining and military operations, which may well increase the risk from asteroids, see Ord (2020).

6 See Ord (2020) for an overview of which risks are most concerning.

7 Where the value of reducing existential risk is around one century of value, Thorstad notes that “...an action which reduces the risk of existential catastrophe in this century by one trillionth would have, in expectation, one trillionth as much value as a century of human existence. Lifting several people out of poverty from among the billions who will be alive in this century may be more valuable than this. In this way, the Simple Model presents a prima facie challenge to the astronomical value of existential risk mitigation.” (p. 5)

References

Thomas Adamczewski (ms). The expected value of the long-term future. Unpublished manuscript.

Leopold Aschenbrenner (2020). Existential risk and growth. Global Priorities Institute Working Paper No. 6-2020

Nick Bostrom (2013). Existential risk prevention as a global priority. Global Policy 4.

Nick Bostrom (2014). Superintelligence. Oxford University Press.

Carl Sagan (1997). Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space. Balentine Books.

Anders Sandberg and Nick Bostrom (2008). Global Catastrophic Risks Survey. Future of Humanity Institute Technical Report #2008-1

Toby Ord (2020). The Precipice: Existential Risk and the Future of Humanity. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Toby Ord (ms). Modelling the value of existential risk reduction. Unpublished manuscript.

Other paper summaries

Summary: When should an effective altruist donate? (William MacAskill)

Effective altruists seek to do as much good as possible given limited resources. Often by donating to important causes like global health and poverty, farmed animal welfare, and reducing existential risks. Can we help more by donating now or later? This is the thorny question William MacAskill tackles in the paper “When should an effective altruist donate?”. He explores several considerations…

Summary: Against the singularity hypothesis (David Thorstad)

The singularity is a hypothetical future event in which machines rapidly become significantly smarter than humans. The idea is that we might invent an artificial intelligence (AI) system that can improve itself. After a single round of self-improvement, that system would be better equipped to improve itself than before. This process might repeat many times…

Summary: Staking our future: deontic long-termism and the non-identity problem (Andreas Mogensen)

In “The case for strong longtermism”, Greaves and MacAskill (2021) argue that potential far-future effects are the most important determinant of the value of our options. This is “axiological strong longtermism”. On some views, we can achieve astronomical value by making the future population of worthwhile lives much greater than it would otherwise have been…