Hilary Greaves | Doing good together: Collectivism vs. coordination

JONATHAN COURTNEY: (00:06) I'm delighted to present our next speaker Professor Hilary Greaves who is a professor of philosophy at the University of Oxford. Her current research focuses on various issues in ethics. Her interests include foundational issues in consequentialism, issues of aggregation, egalitarianism and anti-aggregationist approaches, population ethics, effective altruism, the interface between ethics and economics, the analogies between ethics and epistemology and formal epistemology. She currently directs the project Population Ethics Theory and Practice funded by the Leverhulme Trust and she's also the director of the Global Priorities Institute. Please help me in welcoming Hilary Greaves.

[applause]

HILARY GREAVES: (00:53) The theme of this conference is Doing Good Together. What exactly does this mean? In this I want to disentangle two quite different things that it could mean, but I have to be [inaudible 01:03] with one another if we're not careful. The first one is called collectivism. This has been the focus of an often-repeated criticism of the effective altruist movement over the years. Here the idea is that effective altruism errs in focusing only on what the individual can achieve by themselves as it were and not on focusing on what the community can achieve as a whole. I mean we all notice that this why effective altruists are so into these sticking plaster interventions like distributing malaria nets while they never actually quite fix the underlying problem that caused the need for malaria nets in the first place. Okay. So that's the first idea, collectivism. Quite a different thing is coordination which is about the extent to which we should be talking to one another and making joint plans when we decide what to do.

(01:50) What I meant to be arguing is that the collectivist criticism of effective altruism is confused. I'm going to be arguing that we do not at a fundamental level need to be asking what the group can achieve rather than what the individual can achieve. However, that's not to say that we don't need to be thinking about coordinating. So I think the organizers of this conference when they talk about doing things together are actually mostly or entirely talking about coordination. So they're saying the thing that I agree with. But many critics of effective altruism have been saying the thing I disagree with and it's important that we don’t get sucked into that [inaudible 02:22].

(02:24) So, what are these two ideas? Collectivism as I indicated is the idea that in certain decision situations, in particular in the context of attempting to solve some of the biggest problems that face the world, we find ourselves in this maybe peculiar situation where it's true about the individual who might try to intervene on that problem but that individual’s marginal contribution that makes not only a small difference but actually precisely no difference and to the extent to which the problem gets solved. Whereas when we consider a thousand, a million, a billion people engaging in similar actions simultaneously, now we've got an especially large group that we can make a difference.

(03:05) Many people think this, for example, about the problem of climate change where we consider the question of whether if we're worried about climate change there's a case for each of us individually to try to reduce our carbon footprint. Many people feel some kind of moral pull towards reducing their carbon footprint but at the same time some kind of puzzlement as to whether there really is a point in doing so. And the puzzlement comes from this idea that one individual reducing their carbon footprint is going to make literally no difference to the problem of climate change. This is perhaps arguably suggested by Barack Obama for instance. Obama was asked by one of his constituents, “President Obama I want you to tell me not what you're doing about climate change politically speaking but what are you doing about climate change in your personal life?” To which Obama is reported to have responded, “Well Brian we can't solve global warming because I effing changed light bulbs in my house, it's because of something collective.”

(04:06) Another example where you might think you have this phenomenon (no individual can make a difference but the group can) is in the context of campaigning for revolution, political change, structural reform. So consider for example the 1963 march on Washington. This was an event in which one quarter of a million people marched on the White House demanding black rights. And that event is widely credited with partially bringing about the US 1964 Civil Rights Act. Imagine yourself now in the shoes of one of those people in that mass demonstration. Suppose that you decided whether or not to join the demonstration by asking, “Do I think that my contribution to this demonstration will make a difference?” There too it's at least easy to get into a frame of mind where you think, “No. My joining the demonstration, the difference between a quarter of a million people and a quarter of a million plus one people. That's going to make precisely no difference one might think to the degree of success of the demonstration,” and therefore if each individual was making their decisions on the basis of asking what difference their individual actions would make rather than perhaps by asking the question of what difference the actions of the whole collective would make, maybe the individual would fail to see the case for joining protests like the 1963 march on Washington.

(05:29) So this is the kind of thing that collectivist think. I've tried to present it sympathetically but I still am likely going to be arguing against this. What do I want to contrast it with? So I wanted to draw this distinction between what I'm calling collectivism on the one hand and coordination on the other hand. So let me try now to pull these two things apart. So collectivism again is about what kind of agents we’re focusing on. The collectivist idea is that if you're focusing on individual agents and you're interested in the question of making a difference, then you're going to fail to see the case for action on things that requires say political change because in that case the only kind of agent that can make any difference is a group agent not an individual agent.

(06:11) A quite a different claim, the coordination claim is not about which kind of agents we’re talking about, its instead about which kind of actions we’re considering. So suppose now that we are asking the question of how the individual can best make a difference. There are different kinds of actions the individual might try to take in order to make a difference. Some actions are ones that can be evaluated as it were with the blinkers on, that is to say without paying any attention to anything the other like-minded individuals are doing. Whereas other actions are more collaborative. So you know one thing that you might try to do is fund malaria nets. A different thing that you might try to do say is organize a political campaign where you talk to other potentially like-minded people and try to cause them to do certain things. And so the coordination claim is that we need these individual actions that involve trying to coordinate with other like-minded agenda and other like-minded people to be on the agenda when we're deciding how the individual can best make a difference. So that second thing I'm not going to be taking any issue with, but it’s importantly different from the first thing and I am going to argue against the first thing.

(07:17) First let me convince you that I'm not just attacking a straw man here. So here is a person who says the thing that I disagree with. This is Amia Srinivasan a moral philosopher and the quote is from a piece she wrote called Stop the Robot Apocalypse which is a critical review of William MacAskill’s book Doing Good Better. The robots, by the way, are the effective altruists. So Srinivasan says:

“There is a small paradox in the growth of effective altruism as a movement when it is so profoundly individualistic. The tacit assumption is that the individual, not the community, class or state, is the proper object of moral theorizing. There are benefits to thinking this way.”

She now continues somewhat sarcastically.

“If everything comes down to the marginal individual, then our ethical ambitions can be safely circumscribed; the philosopher is freed from the burden of trying to understand the mess we're in or proposing an alternative vision of how things could be.”

(08:11) Okay. So there the bit that I've put in boldface and underlined is this idea that what the effective altruist is doing is talking about individual agents and not group agents and then from that she draws the consequence that this is why the effective altruist fails to see the case for political change and just obsesses about malaria nets all the time.

(08:32) What's the right response to that sort of criticism? First I want to highlight two short responses that might be and have been given, but I only want to mention these in order to set them aside.

(08:44) The first short response would be to say that this criticism attacks a straw man, that is to say, it's not in fact true that effective altruists ask only what individual agents can achieve and not on what group agents can achieve. I think there's some truth to that but as I said I want to set it aside.

(09:02) I also want to set aside a second short response one might give. It's also something I have some sympathy with although it's incompatible with the first. The second short response says, “Well, you know, it's true that effective altruists only asking what difference the individual can make, however, they're correct to do so.” So this suggestion is floated by Jeff McMahan in his responses to Srinivasan. McMahon says look I am neither a community nor a state. I can determine only what I will do not what my community or state will do. So that is the idea. You know, yeah, maybe it is true that the individual can't make any difference to issues of political reform but if so that's a very good reason for not trying to do so. I can only affect my own actions so that is indeed the thing I should be focusing on.

(09:47) I think there's a lot more to be said about both of these responses and I don't necessarily disagree with either of them, but the reason I want to set them aside is that they implicitly concede too much to the collectivist critique and I think the thing we should be really doing is pushing back on the more fundamental thing in the collectivist picture. The thing that it concedes and should not concede is that the collectivist conditional claim is true and the conditional claim is, if you were focusing only on individual agents then that would necessarily lead you to fail to see the case for action on political change. That's the thing I think we should more fundamental push back on.

(10:22) So let me have a go at doing that. To do so I want to pull a trick that philosophers often pull and often annoys non-philosophers. So they say what the trick is, they don’t say why you shouldn't be annoyed by this. It's a reasonable thing to be doing. The trick is to retreat temporarily from all the messy complexities of real-world scenarios and stipulate that we're talking about a very clean simple hypothetical case. So I'm going to be talking about an imagined world bearing some resemblance for the real world but because it's my own imagined world I get to stipulate away various complexities of how things actually pan out in the real case. The motivation for doing this is it's a tool for clarification. It's a bit like when the physical scientist, you know, fundamentally wants to investigate something like the laws of Newtonian mechanics but if he tries to do that in the real world, there's all kind of mess going on. You know, there's wind interference, there's friction, blah blah blah. So instead of trying to do your experiments in a field, you construct a laboratory where you can screen off lots of the complexities, investigate things in a more simple scenario and then use the understanding you thereby gain to figure out better what's actually going on in the real world. So the philosopher is just doing an analogue of that thing. Let us talk about the simple cases first, so we can clarify the fundamentals, then we'll go back to the real world hopefully with a superior level of understanding.

(11:40) Okay so here's the hypothetical case I want to talk about. A case of vegetarianism. Suppose for the sake of argument we all agree that chicken deaths are bad and suppose that for this reason if the situation we were in was one of having to go to the farm and saying to the farmer, “You know, I fancy a chicken for my dinner tonight, so please kill that one there.” And then the farmer duly wrings the neck of a chicken and we take it home and cook it for dinner. Suppose we all agree that in that decision situation we would not buy the chicken because we think that whatever pleasure we might get from eating chicken is massively outweighed by the amount of badness involved in the chicken death.

(12:18) Okay. So far so good. What now in a different decision situation, one that's actually a bit more like the one we are actually in when we consider buying chicken? It's vegetarianism in the supermarket. So consider now a case where the setup is such that when you get to the supermarket you consider whether or not to buy a chicken from the butcher's counter and suppose for the sake of argument you know that the way the supermarket works is it's going to order another 25 chickens from say the farm, the slaughterhouse, with the result that another chicken 25 chickens will be killed every time the 25th chicken is sold. So if you're, say the 3rd or the 29th person, you buying a chicken doesn't trigger any more chicken deaths, but if you happen to be the 25th person or the 50th person, that triggers another 25 chicken deaths. So suppose that many people buy one chicken each you're considering whether or not to join their ranks and for the sake of argument let's stipulate that on the day in question precisely 578 people buy a chicken from the supermarket in question. But no individual knows this, so you as the individual shopper at the time of your decision don't have access to that information, you just know it's a pretty big supermarket and who knows how many chicken purchases there are going to be in total.

(13:) Okay. So the question now is, do you still have the same kind of reason in this decision situation to refrain from buying a chicken as you did in the situation where you had to buy it from the farm and directly cause its death? It looks like the situation might be relevantly different or at least the collectivist thinks it is. So the collectivist thinks, “No. In the supermarket case, if you're asking about the effect of the marginal individual, you're just asking what difference you make by buying chicken but you won't see the case as being vegetarian because it's overwhelmingly unlikely at least in that scenario that your buying one chicken is going to make any difference at all to the number of chickens that get killed”. However, [inaudible 14:10] difference to the number of chickens that get killed if this whole big group of 578 people chooses to buy chickens versus not. So you might think that this is a case that by collective [inaudible 14:22] like is relevantly similar to a situation of say joining a campaign for political reform.

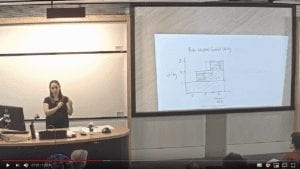

(14:31) Alright. So I'm going to be arguing against this picture. Before I do so, maybe some people will find helpful if I just draw it on a graph.

(14:37) So in this graph the vertical axis represents the total amount of harm done by all chicken purchasers put together. So in this case total amount of harm done is a number of chicken deaths while the horizontal axis represents the total number of people including yourself, if you join in, who buy chickens on the day in question. What does that graph look like? Well in the case of the farm it was pretty much a straight line each extra person buying one chicken caused a small increase in the amount of harm. That was the straightforward case. What's happening in the case of the supermarket is that we have this staircase function. So most individuals, if they're in the location of the first white arrow on that screen, what most marginal individuals do if they buy a chicken is just shift slightly along one of the horizontal steps. So they increase the number of chickens that get bought but they don't even by a tiny amount increase the amount of chicken suffering or the number of chicken deaths. Whereas, if you happen to be the 25th person or the 50th or the 75th then you caused 25 extra chicken deaths because you cause us to go up another step on the staircase function.

(15:45) Okay. So that's just saying the same things on the graph. How should we think about these decisions?

(15:52) So what I want to try and convince you of is that the way the collectivist is thinking… When the collectivist draws this model that this is a situation where no individual makes a difference and yet the collective does, so we have to be thinking and irreducibly about group agents in order to see the point of being vegetarian. That picture is confused and the reason it's confused is it's confused about the question of what's the right approach to decision making under uncertainty? When you think carefully about how to make rational decisions, when you're uncertain as you are here about what the outcome of your decision will be, the standard answer is that we're not to maximize expected value. What do we mean by that? Well we mean that the rational decision-maker is supposed to consider in turn all of the possible outcomes of their actions. In this case there are two possible outcomes, zero additional chicken deaths or 25 additional chicken deaths. Then you're supposed to assign probabilities to these various possible outcomes and you're supposed to assign numbers to the outcomes representing how good or bad they are, so assign values to the outcomes. And then you're supposed to choose whichever action, in this case buying the chickens or not, maximizes “expected value” where expected value is the probability weighted average of the possible values that might result from your action. So when we do this calculation for the vegetarianism in the supermarket example, what we end up doing is first saying well there was a chance of 24 out of 25 that my action resulted in no additional chicken death. So that's 24/25 times zero. Okay that part's zero, however, I have to add 1/25 multiplied by the badness of 25 chicken death because I have a chance of 1/25 of causing 25 more chickens to be killed. What's the result of that calculation? Well it means that the expected badness resulting from my purchase is equivalent to one chicken death, that is to say, from the point of view that's relevant for rational and moral decision-making, there is in the end no relevant difference between the case of buying a chicken directly from the farm and the case of buying a chicken from the supermarket, at least the simple way that I've stipulated the case goes for my example.

(17:58) So because of this I think it's just not true in any sense that's relevant to decision that the individual makes no difference. The individual’s action does make a difference to the amount of expected value in the world and once you recognize this you have no remaining sense of the so-called collectivist paradox.

(18:16) Okay. What about the real world? Maybe there's one more thing I should say about chickens before I go back to political reform cases. You can imagine a situation in which it really would be true or at least it looks like it really would be true that the individual makes no difference. That would be a situation in which the individual is already certain at the time of decision not only what shape this graph has specifically that the steps occur precisely every 25 purchases, but is also sure of how many other chicken purchasers there will be today other than herself. If you were in that epistemic situation and if it was in fact true that the chicken deaths get triggered every 25 chicken purchases and that the number of chicken purchasers besides yourself is, say 578, then you really could be sure that you're buying a chicken would make no difference to the number of chicken deaths. And furthermore it could be the case that every other person in that supermarket is in the same epistemic situation. So it could be true of all 579 of you at the same time that none of your individual actions makes any difference to the number of chickens who die and yet the actions of the collective do. So I'm not ruling out that possibility.

(19:23) The important question for our purposes though is which of these possibilities is more relevantly similar to the scenarios we're actually interested in, which are things like real-world versions of the vegetarianism case on the one hand but also things like political reform, joining mass demonstrations, organizing mass demonstrations, that kind of thing on the other hand.

(19:47) I think it's just completely implausible to suppose that cases like climate change and political reform are relevantly similar to the nice clean version of the vegetarianism case where you can be absolutely certain that your action has no difference. Consider for a minute what it would take for that to be the case. It would have to be the case for the march on Washington firstly that they knew the graph, of the degree of success of a political campaign graft against the number of people who take part in the demonstration.

(20:17) Okay. We know that graph has a kind of upward trend, right, because we know that in general very large political demonstrations get taken more notice of than very small political demonstrations. It is important all that the march on Washington included a quarter of a million people and not two and a half thousand people. But what we don't plausibly know is precisely where the steps occur on that graph, and even if we did it wouldn't be any help to us because no individual demonstrator when deciding whether or not to join the demonstration has any precise idea of how many demonstrators there will end up being aside from herself. So for both of these reasons the situation she's in is the situation of decision making under uncertainty where she's forced to evaluate her individual actions in expected rally terms and as soon as you are doing that you're going to see the case for individual action on these complex questions even if you are just focusing on individual agents and not on group agents.

(21:14) Okay. So in conclusion then what I've argued is that asking only what difference the individual can make rather than what difference the group can make should not prevent you… If you're doing your reasoning correctly it should not prevent you from capturing the case for collective action on things like political reform and climate change.

(21:33) I want to add a small conciliatory remark. I mean here's a thing that I think is true. As a psychological matter it may well be easier to grasp, it may well be easier to accurately evaluate the expected value of your individual actions if you ask yourself the question of, “Well you know, what would happen if a million people did this?” If you can magnify things by a factor of a million in your mind they become much bigger, that makes them much easier to see. It might be the case that when you consider that question your intuitions are more accurate. So there might be that kind of psychological reason for imagining the scaled up collective version of the question, but acknowledging that as importantly distinct from getting the underlying logical point wrong. The underlying logical point is that if you could do the reasoning correctly, then you would get the right answer. You would see that in expectation, individuals make a difference even when you do just consider the case of the effects of the actions of one person taken separately.

(22:26) The thing I'm not denying though is the coordination claim. So this, as I mentioned at the beginning, is the claim that we'd better not have too blinkered an approach to the question of what kind of actions should be on the individual’s agenda. It may well be the case that the best thing that you as an individual can do in expected value terms, that is, in terms of how much expected value you, by your individual actions, can add to the world, it may well be that the actions that win that expected value competition are actions that involve coordinating with other potentially like-minded people rather than actions that are more unilateral, whatever precisely that would mean. So certainly these actions that involve coordination have to be on the effective altruists agenda. But acknowledging that is not the same thing as saying that we have to be thinking irreducibly in terms of the agent being the collective rather than a group of individuals.

Thanks.